Vision Needs a Seat at the Negotiating Table

By Bill Becker

June 2012

When American theorist Buckminster Fuller said, “[we] are called to be architects of the future, not its victims,” he may not have known how difficult a challenge that would become in the years following his death.

In the second decade of the twenty-first century, the architecture we need to solve global problems—including the barriers to a more sustainable civilization—is as daunting as the problems themselves. It requires unprecedented levels of international collaboration, new institutions and systems, and the courage to confront threats not only to everyday life but to the natural systems that support life itself. Mere transactions are not sufficient. In the words of businessman and entrepreneur Sam Walton: “Incrementalism is innovation’s worst enemy. We don’t need continuous improvement, we want radical change.”

Although he might not have imagined how great the challenge would become, Fuller’s analogy remains instructive. Let’s think about what architects usually do. First, they have a conversation with their clients to learn their needs and wishes. That conversation is an exchange of information: a combination of the client’s requirements and the architect’s knowledge of the latest and best designs in the building business. Next, the architect renders one or more design options. Once the client approves, the architect draws up the plans that will guide the engineers and contractors who do the construction.

Apply this process to world affairs with the world’s people as clients, sustainable development as their requirement, the United Nations as the architectural firm, and international negotiators as the architects. It appears that two critical elements in the process need to be improved: dialogue with the clients, and rendering the designs they have seen, understand, and want.

In the context of the United Nations work on sustainable development, including the June 2012 Rio+20 Conference, there has been a great deal of consultation with stakeholders but until now, not at the level of a true global conversation. In addition, design renderings—in this case visualizations of sustainable societies—have not been a significant element in negotiations. Yet, we have extraordinary capabilities for global dialogues and a vision that we did not have when the first Earth Summit was held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. Widespread public access to the Internet’s information super- highway did not exist then, nor did the many social media that allow conversations to take place without boundaries in real time. Consultation between policymakers and the people around the world whose futures are at stake has never been as possible as it is now.

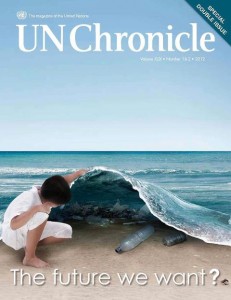

Meanwhile, communications technologies and visual arts have advanced so far that it’s often difficult to distinguish reality from virtual reality. The entertainment industry uses these technologies to take us to imaginary worlds; the advertising industry uses them to entice us into new desires. If a picture is worth a thousand words, then the pictures we are able to generate today can be infinitely more valuable in reaching the public than policy documents on topics as abstract as sustainable development. As Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said on 22 November 2011: “We need to imagine a different future. What would our world look like if everyone had access to the food they need, to an education, and to the energy that is required to develop? What would our communities look like if we created a vibrant, job-rich, green economy? This is the future we want.”

It is not that visions of the future are absent from society; rather, visions of the negative kind tend to dominate popular media. Think of the documentary film The 11th Hour, the movies The Day After Tomorrow and The Road, or the nightly news images of economic collapse, war, homelessness, joblessness, and the brutal treatment of people by their Governments. The problem is that the images of the future we must avoid are not balanced with the images of a future we can build.

Unbalanced negative vision has its own power, and many advocates of sustainability have embraced it. The noted British environmentalist Jonathon Porritt chastises his peers for focusing only on ecological collapse rather than on the advantages of living within the ability of natural systems to sustain us. “For wholly understandable historical and intellectual reasons, today’s environmental discourse is still shaped far more powerfully by the language of scarcity and limits than it is by any compelling upside narrative,” he writes. “But fear of the future does not empower people; it debilitates and disempowers.”

Other observers have noted that the dominance of fear in our media produces apocalypse fatigue, which is the tendency for people to withdraw from action on problems that seem overwhelming. At that point, apocalypse becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The impact of positive vision is quite different. An emotional connection with the upside of a more sustainable world can foster public support, which, in turn, can produce the political will that is so critical in fulfilling the aspirations of Agenda 21 or the Millennium Development Goals.

Based on assumptions like these, a group of experts in communications and sustainable development met in New York in 2009 to diagnose the missing elements in the global conversation about the future. The result was a project called The Future We Want, which has evolved into two major parts.

Part One is a global conversation—an invitation for people around the world to use the Internet and social media, or drawings and letters, to tell us what they want their lives and communities to be like 20 years from now. In Part Two, some the world’s best visual artists, along with experts in sustainable technologies and designs, will use the results of the global conversation to create visualizations of sustainable communities in different countries and cultures. We will unveil the visualizations in an exhibit at the Rio+20 Conference.

Since the Secretary-General’s announcement in November 2011 that The Future We Want would be the tagline for Rio+20, the phrase has been catching on around the world. The Secretary-General has embraced the phrase as a theme of his agenda for the next five years. The Zero Draft—the outcome document for Rio+20—carries The Future We Want as its title, and youth organizations including Peace Child and the Road to Rio+20 have adopted The Future We Want theme for a World Action Day prior to the conference.

Fortunately, The Future We Want project is not alone in mobilizing the power of positive ideas and visions. My Green Dream, an initiative of the United Nations Institute for Training and Research and the Network of International Training Centers for Local Actors, is collecting short videos in which people around the world talk about their aspirations for the future. Sustainia, a project of the Danish think tank Monday Morning, is conducting a contest to identify the 100 best ideas to achieve sustainability by 2020. The Institute for Transportation and Policy Development in New York has a project called Our Cities Ourselves, in which prominent architects have drawn what sustainability might look like in cities in China, India, Brazil, Argentina, Indonesia, Mexico, Hungary, Tanzania, and South Africa. America 2050, a project of the Regional Plan Association in New York, has produced a video, Journey to Detroit, showing what life might be like for a commuter in the future.

Corporations are also in the vision business. Arup, the international development company, uses video to show what infrastructure might look like in the future. Corning has produced a film called A Day Made of Glass, showing how its products will make life easier. Siemens and its competitor, General Electric, have created their own visions of the future.

Other groups have created tools to interact with sustainable development scenarios as a way to experiment with different futures. One, produced by United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the Government of the United Kingdom, allows people to make changes to their virtual homes and businesses, and then computes the carbon impacts. Urbanology, produced by the Guggenheim Laboratory, asks eight questions about how you would plan your ideal city, and then tells you how it would operate. For those who believe we’ll need a superhero to get to the future we want, Pixton offers a web-based tool to create comic strips and to share them with the world on Facebook and Twitter.

However, there are barriers to visualization as a tool of policy and progress, and there are some basic requirements for making vision effective. One barrier is that policymakers may discount vision as fluffy, dreamy, and insubstantial. For those engaged on the world’s policy battlefields, taking visions to the negotiating table may seem the rough equivalent of going into battle with marshmallows rather than bullets. However, positive visions have power. To exercise that power, vision and visualizations must meet a few standards. They must be realistic. They must show us visual answers to questions such as “How will communities mitigate climate change and adapt to what’s already inevitable?”, “How will cities cope with rapid urbanization?” or “Is a net zero carbon neighborhood a place I’d like my family to live?” They must depict a future that’s reachable from here—not too far from now and not too fantastic. Many of the best visualizations right now show today’s cities being retrofitted for greater sustainability.

Visualizations should be culturally sensitive rather than project only a Western model of life and cities. In fact, one of the most important uses of place-based visualizations of sustainable cities is to change how we define success in economic development and quality of life.

A global conversation must also meet some standards. It should include the many people around the world who don’t have access to the Internet or to social media, whose voices are not often heard. That’s a task The Future We Want hopes to address with the help of the United Nations network of offices and of international organizations that work in remote places.

Our challenge and obligation is to use our unprecedented tools to engage the people who are building the future and those who will inherit it, in its design. As the late American environmental scientist Donella Meadows noted: “If we haven’t specified where we want to go, it is hard to set our compass, to muster enthusiasm, or to measure progress… (yet) vision is not only missing almost entirely from policy discussions; it is missing from our culture. We talk easily and endlessly about our frustrations, doubts, and complaints, but we speak only rarely and sometimes with embarrassment about our dreams and values.”

Faced with an array of global challenges that will greatly limit our choices for the future if left unaddressed, there is no time to be embarrassed about the dreams, values, and visions that will help us create the future we want. It’s time to invite vision to the negotiating table.

###

To join the global conversation about the future we want, go to http://www.futurewewant.org, to Facebook at htttp://facebook.com/futurewewant, or to Twitter at @futurewewant.

vvlx,

hentai,

xporn,

xnxx,

sex việt,

Family Practice Doctors Near Me,

Ratify Treaties,

Best Hookup Apps,

Brunch On A Wednesday,

Comfortzone,

Plaza Premium Lounge Orlando Reviews,

Catering 77002,

Cauliflower And Coconut Curry,

Usa Rail Pass,

Active Duty Service Member,

Patch American Flag,

Farfetch Coupon Code,

Connect Google Mini,

Nike Mens High Top,

Bronny James Usc Basketball,

Anal Sex Prep,

Aesports,

Check Balance On Debit Card,

Add People Trustpilot,

Skype Ids,

← Rio+20 – The Young Can’t Wait

The Doughnut can Help Rio+20 see Sustainable Development in the Round →