Eric William Carroll: Mourning darkroom’s demise

By Andrew Wallace Chamings

By Andrew Wallace Chamings

May 10, 2012

Eric William Carroll is mourning the death of the darkroom.

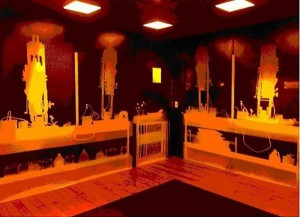

Carroll, the recipient of the 2012 Baum Award for an Emerging American Photographer, is using his new show at SF Camerawork to pay homage to his favorite space. The centerpiece of the show is called “This Darkroom’s Gone to Heaven,” a full-size group darkroom in which white shadows replace equipment and intellectual discourse will replace photographic development. It will host meetings of guest photographers talking about dead photographers and dead techniques.

Beyond the familiar nostalgia for the amber light and the noxious scent of sulfur dioxide, Carroll pines the loss of the darkroom on a more human level.

“The darkroom is becoming an endangered habitat,” he says, adding that with “Darkroom,” he’s “trying to qualitatively measure what we’re losing with the disappearance of such a space. The greatest loss is the sense of community. … It’s like a bar for photographers. We’re all there to focus on our work, but we share stories, learn tricks of the trade and ultimately bond by honing our art in the same space.”

His “Darkroom,” he says, looks as though “a bomb had gone off, vaporizing everything and leaving only shadows where the objects stood. Having lost its function, the darkroom opens itself up to be repurposed.”

The San Francisco photographer says he’s always contended with the idea that photography may be nothing more than a futile attempt to record and re-create natural phenomena. But he admits that it doesn’t come easy. In a 2009 essay called “The Crisis of Experience,” Carroll wrote: “The reason I took photography as my subject, like many before me, is because of the overall uneasiness I feel towards the medium, almost a sort of crisis.”

The SF Camerawork show comes on the heels of “Plato’s Home Movies,” Carroll’s show last fall at S.F.’s Rayko Photo Center. In that show, Carroll created a 60-foot blueprint photogram mural depicting the light and shadows in woodland. The piece challenged the understanding that photographs are meant to preserve.

Carroll used photographic techniques from a time when the ability to “fix” and archive an image was not yet achieved. Using light-sensitive paper, the show itself changed throughout its stay at the space as the San Francisco sun, bursting through the south-facing South of Market windows, slowly “destroyed” the original image – meaning viewers would experience a new memory on each visit.

It’s hard to ignore the philosophical undertones to Carroll’s preoccupation with the brevity and fragility of the art form. Beyond a timely comment on passing technology, there is a sadness and beauty in every piece. The unnatural interior of the lowly lit darkroom, in the center of the pale light of the gallery space, has something approaching a purgatorial ambience. And in the SF Camerawork show – a collection of selected work spanning the past six years – every piece on show, from Carroll’s cyanotypes based on drawings by Henry Fox Talbot to an enlarged fogged negative, provides a comment on the loss of the human element in photography.

“This sentiment echoes throughout the rest of the work in the show, often through the idea of human error and the great lengths we go to cover up or fix these supposed errors,” he says. “To me, the error is a charming reminder that humans haven’t been deemed obsolete just yet.”

Reception 5 p.m. Fri. Through June 30. Noon-6 p.m. Tues.-Sat., until 7 p.m. Fri. SF Camerawork, # 2, 1011 Market St., S.F. (415) 487-1011. www.sfcamerawork.org.

vvlx,

hentai,

xporn,

xnxx,

sex việt,

Family Practice Doctors Near Me,

Ratify Treaties,

Best Hookup Apps,

Brunch On A Wednesday,

Comfortzone,

Plaza Premium Lounge Orlando Reviews,

Catering 77002,

Cauliflower And Coconut Curry,

Usa Rail Pass,

Active Duty Service Member,

Patch American Flag,

Farfetch Coupon Code,

Connect Google Mini,

Nike Mens High Top,

Bronny James Usc Basketball,

Anal Sex Prep,

Aesports,

Check Balance On Debit Card,

Add People Trustpilot,

Skype Ids,